Ticks & Diseases Info

Lyme disease andearly summer meningoencephalitis (TBE) are the most common tick-borne diseases in Austria. Rarely,anaplasmosis,tick-borne relapsing fever-Borreliosis throughBorrelia miyamotoi,neoehrlichiosis,rickettsiosis,babesiosis, andalpha-gal syndrome.Tularemiais usually a contact infection but is very rarely also transmitted by ticks in certain areas.Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever has not yet been observed in Austria.

Lyme-Borreliosis

Lyme disease is an infectious disease caused by bacteria of the genus Borrelia. It is the most common tick-borne infectious disease in the Northern Hemisphere. Over 30 percent of Ixodes ricinus ticks(common wood tick; most common tick species in central and northern Europe) are infected with Borrelia.

Early summer meningoencephalitis (TBE)

Early summer meningoencephalitis (TBE), also called tick-borne encephalitis, is caused by the TBE virus found in the saliva of some ticks. The tick transmits the viruses immediately after being bitten. The TBE virus multiplies in human nerve cells. The disease is notifiable.

Crimean-Congo fever

Crimean-Congo fever is a viral disease that can be fatal. The viruses are mainly transmitted by Hyalomma ticks. Hyalomma ticks are originally native to warmer regions of southeastern Europe and Asia, and adult specimens have also been found in Austria for several years.

Tularemia

Tularemia (rabbit plague) is a bacterial infectious disease that can be transmitted from animals to humans. Ticks, play an important role in maintaining the incidence as vectors.

Pathogens from A to Z: Tularemia (Rabbit Plague)

Alpha Gal Syndrome

Information on Alpha-Gal Syndrome

This allergy to the sugar galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose (alpha-gal) is caused in some people by the bite of certain tick species. Alpha-gal syndrome was first described in the USA in 2009. Subsequently, this form of allergy has been detected in people on other continents, including Europe (Sweden, Norway, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, France, Austria).

Symptoms

Reactions occur 3 to 7 hours after consumption of mammalian products (red meat, gelatin, dairy products, etc.), beginning with severe itching, often over the entire body, sometimes accompanied by skin rashes (urticaria). Severe reactions may include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea (diarrhea), swollen hands, and even respiratory distress, hypotension, and fainting (anaphylactic reactions).

Prevention

There is no specific therapy for this allergy. Patients are advised to avoid red meat (beef, pork, sheep, game, etc.) and gelatin. If dairy products also cause symptoms, these should also be avoided. Affected patients are usually prescribed an emergency kit with medication.

Occurrence in Austria

Cases acquired in Austria are known.

Sources

Hoepler W, Markowicz M, Schoetta AM, Zoufaly A, Stanek G, Wenisch C. Molecular diagnosis of autochthonous human anaplasmosis in Austria - an infectious diseases case report. BMC Infect Dis. 2020 Apr 19;20(1):288. Markowicz M, Schötta AM, Wijnveld M, Stanek G. Lyme Borreliosis with Scalp Eschar Mimicking Rickettsial Infection, Austria. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020 Sep;26(9):2193-2195.

Markowicz M, Schötta AM, Penatzer F, Matscheko C, Stanek G, Stockinger H, Riedler J. Isolation of Francisella tularensis from Skin Ulcer after a Tick Bite, Austria, 2020. Microorganisms. 2021 Jun 29;9(7):1407.

Petrovec M, Schweiger R, Mikulasek S, Wüst G, Stünzner D, Strasek K, Avsic Zupanc T, Marth E, Sixl W, poster presentation P-5, International Conference on Rickettsiae and Rickettsial Diseases, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2002.

Polin H, Hufnagl P, Haunschmid R, Gruber F, Ladurner G. Molecular Evidence of Anaplasma phagocytophilum in Ixodes ricinus Ticks and Wild Animals in Austria. J Clin Microbiol. 2004; 42: 2285–86.

Reiter M, Schötta AM, Müller A, Stockinger H, Stanek G. A newly established real-time PCR for detection of Borrelia miyamotoi in Ixodes ricinus ticks. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2015;6:303-8.

Schötta AM, Wijnveld M, Stockinger H, Stanek G. Approaches for Reverse Line Blot-Based Detection of Microbial Pathogens in Ixodes ricinus Ticks Collected in Austria and Impact of the Chosen Method. 2017, Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2017; 83:e00489-17.

Sixl W, Petrovec M, Schweiger R, Stünzner D, Wüst G, Marth E, Avsic Zupanc T, poster presentation P-2, International Conference on Rickettsiae and Rickettsial Diseases, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 20.

Sonnleitner ST, Fritz J, Bednarska M, Baumgartner R, Simeoni J, Zelger R, Schennach H, Lass-Flörl C, Edelhofer R, Pfister K, Milhakov A, Walder G. Risk assessment of transfusion-associated babesiosis in Tyrol: appraisal by seroepidemiology and polymerase chain reaction. Transfusion. 2014;54:1725-32.

Stanek G, Strle F. Lyme borreliosis–from tick bite to diagnosis and treatment. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2018;42:233-258. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fux047.

How to protect yourself from tick bites

There is no absolute protection against tick bites. If you are in tall grass, bushes or undergrowth, wearing closed clothing (sturdy shoes, long pants, long sleeves) offers some protection. This makes it more difficult for a tick to find a suitable skin site for a blood meal. In addition, if the pant legs are tucked into the socks, the tick is forced to walk up the clothing, making it easier to find. Pants and socks should be a light color to help detect dark ticks. A head covering is recommended for children. Applying insect repellent to exposed skin also provides some protection and may reduce the risk of a tick bite. If suitable (no staining), repellents (repellent harmless substances to repel ticks) should also be applied to clothing.

If necessary, supplement the hiking or excursion first-aid kit with a pair of pointed, sturdy tweezers to be able to remove attached ticks immediately.

Avoid contact! Move on wide paths on the well-trodden, middle part of the path. Avoid bushes and thickets and do not walk through tall grass.

Vaccination

There is a vaccination against early summer meningoencephalitis (FSME), which is recommended according to the Austrian vaccination schedule.

Body and clothing control

Since ticks do not bite immediately, but first walk around on the body or clothing in search of a suitable bite site, they can be removed by regular scanning even before they bite. After a bite, it takes up to two days for borrelia to be transmitted. Timely removal of ticks therefore significantly reduces the risk of infection with Borrelia. In contrast, transmission of TBE viruses occurs within a short time after the bite.

After an outdoor excursion, the body should be systematically checked for attached ticks, especially at the preferred biting sites: Pubic area, inner thigh, belly button and surrounding area, under the breasts, armpits, shoulders, neck and nape, hairline, auricle and behind the ears, in the back of the knee and crook of the arm.

Pay special attention to larvae and small nymphs as well: they are very small and can be easily overlooked because they look almost like freckles.

Children should definitely be scanned by adults, especially on the head and neck.

Since ticks do not bite immediately, they could possibly be washed off by showering. However, showering cannot replace scanning, but should only be done as a supplement. If the tick has already bitten, showering is in no case suitable to remove the tick.

After spending time outdoors, change your clothes and remove attached ticks from worn clothing, for example with a clothes roller. Hang damp clothing to dry, as ticks survive in it for several hours. Clothes dried in the dryer are free of ticks.

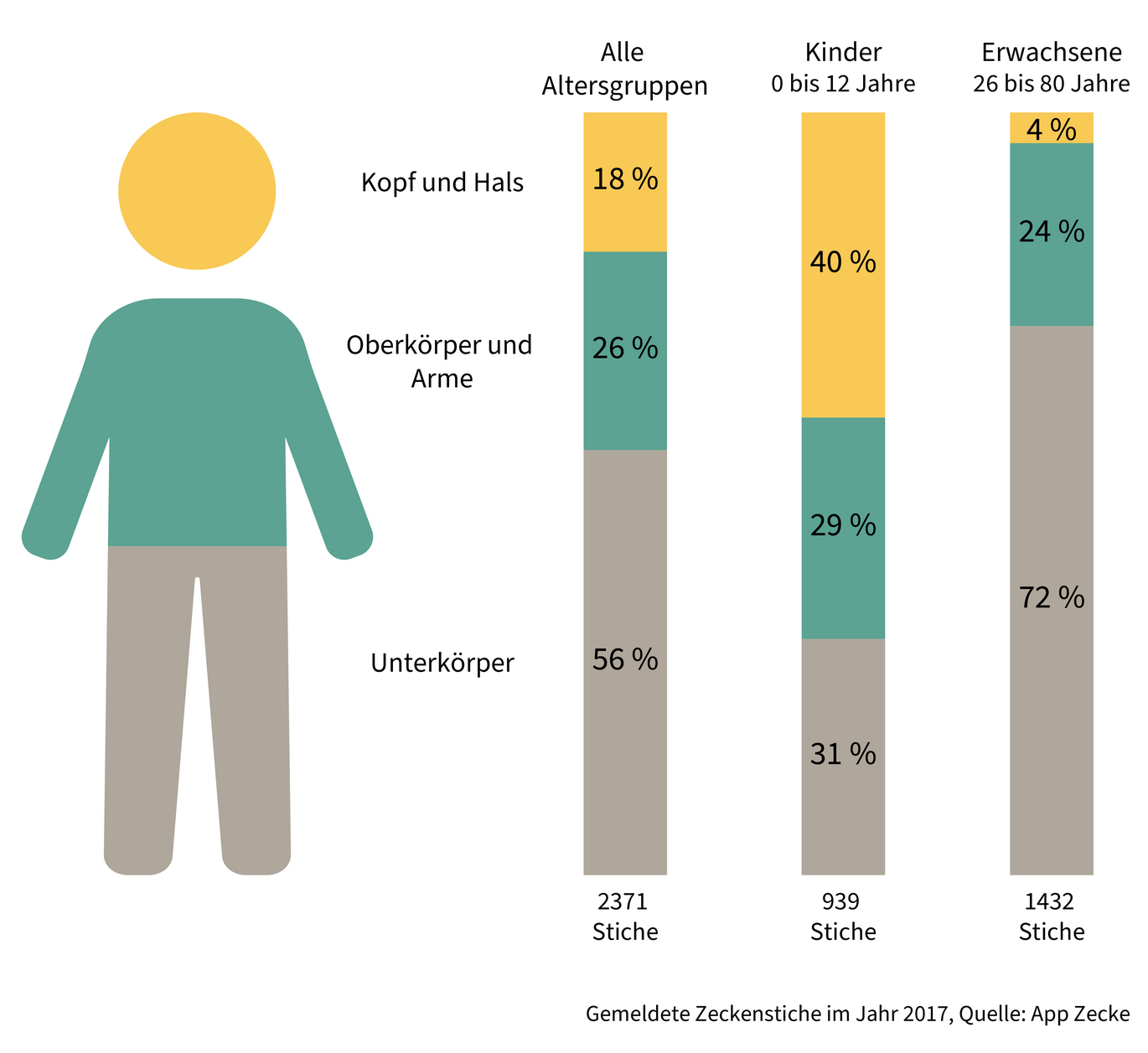

Where ticks bite:

Pets transport ticks into the house

Caution is advised with dogs and cats, they can carry ticks picked up outdoors into the apartment/house. Therefore, they should also be given repellents to repel ticks when outdoors in the countryside and should be checked for attached ticks.

Preferred biting sites in dogs

A study(Duscher et al. Parasites & Vectors 2013, 6:76) analyzed the bite sites of 700 ticks on 90 dogs. The areas colored red represent the areas with more tick findings, and the blue areas were found to have lower tick densities. It is noticeable that the dogs' heads, necks and chests are mainly infested. These are also the localizations where the ticks reach their host. Unlike in humans, where the ticks first have to find their way through clothing, in dogs the ticks crawl along the hair to the skin and bite in without wasting much time.

Remove ticks correctly

To remove a tick safely, use tapered tweezers and grasp it as close as possible to the bite apparatus. The tick can be loosened more easily by turning it slightly or moving it back and forth. The direction of rotation does not matter as the tick has no thread. However, the movement helps to loosen the barbs more easily. Alternatively, you can pull the tick out evenly. Any remains left in the skin are rejected by the skin itself as foreign bodies.

If signs of illness occur several days or weeks after the tick has been removed, such as reddening of the skin, fever, headache or joint pain, a visit to the doctor is necessary.

Do not suffocate

Do not use oil, wax, glue, nail varnish remover or other substances to remove ticks. This would unnecessarily irritate the animal and could cause it to release its saliva and thus possible infectious agents.

Removing ticks from pets

Ticks can be removed from pets in the same way as from humans.

Dispose of ticks correctly

Fold the tick into an adhesive strip, e.g. TIXO, and dispose of it in the household waste, not in the compost.

Ticks: Biology and zoology

Ticks(Ixodida) belong to the class of arachnids and subclass of mites. Adults (adults) have eight legs, and the body is lenticular in shape. Since ticks are parasites, they need another organism as a host to survive. Therefore, they suck blood from vertebrates and can be vectors (transmitters) of disease.

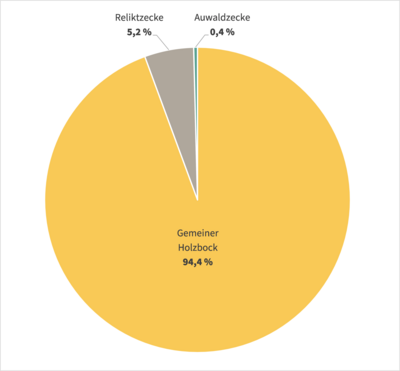

Tick species in Austria

So far, 18 native tick species have been described in Austria, the most common being Ixodes ricinus (common wood tick), Dermacentor reticulatus (floodplain tick) and Haemaphysalis concinna (relict tick). In addition, another species can be introduced via vacation trips with pets: Rhipicephalus sanguineus (brown dog tick). Furthermore, two other tick species can reach us, e.g. via migratory birds: Hyalomma marginatum and Hyalomma rufipes.

Regarding species composition, Ixodes ricinus (common wood tick) represents about 95 percent of the tick fauna in Austria. There is a seasonal sequence in the activity of ticks: The first of the year to be encountered is the more cold-tolerant floodplain tick(D. reticulatus), followed by the common wood tick(I. ricinus). During the hot summer months, their activity declines somewhat and the relict tick(H. concinna) can be found on domestic animals, for example.(Duscher et al. Parasites & Vectors 2013, 6:76)

First evidence of Hyalomma marginatum

In October 2018, the tick species Hyalomma marginatum (tropical giant tick) was detected in Austria for the first time. This 5 to 6 millimeter tick is a vector for rickettsia (bacteria) and Crimean-Congo fever virus (CCHFV). Our molecular biology studies did not detect any virus; however, Rickettsia aeschlimannii was detected for the first time in Austria in the detected specimen. Since 2018, 17 specimens of the tropical giant tick have been detected in Austria.

If you think you have found a tropical giant tick, please send a photo via email to zecken@ages.at.

Family: shield ticks (Ixodidae) Occurrence: widespread throughout Europe (entire European continent from the islands and peninsulas in the north, across the entire mainland to the southern Mediterranean) Activity focus: spring/early summer, late summer/early fall Carriers of: borrelia, TBE viruses, anaplasma, rickettsia, babesia, Francisella tularensis

Family: shield ticks (Ixodidae) Occurrence: from Western Europe, the British Isles through Central and Eastern Europe to Central and Eastern Asia, not in Northern Europe and not in the Mediterranean region Activity focus: early summer, late summer/fall Vectors of: babesia, TBE viruses, Francisella tularensis, rickettsiae

Family: shield ticks (Ixodidae) Occurrence: North Africa, European Mediterranean region, west and center of Asia, south of Russia, Pakistan and Turkmenistan, in October 2018 for the first time in Austria Special features: relatively large with body length of about 5 to 6 millimeters Carriers of : Crimean-Congo fever virus, rickettsiae

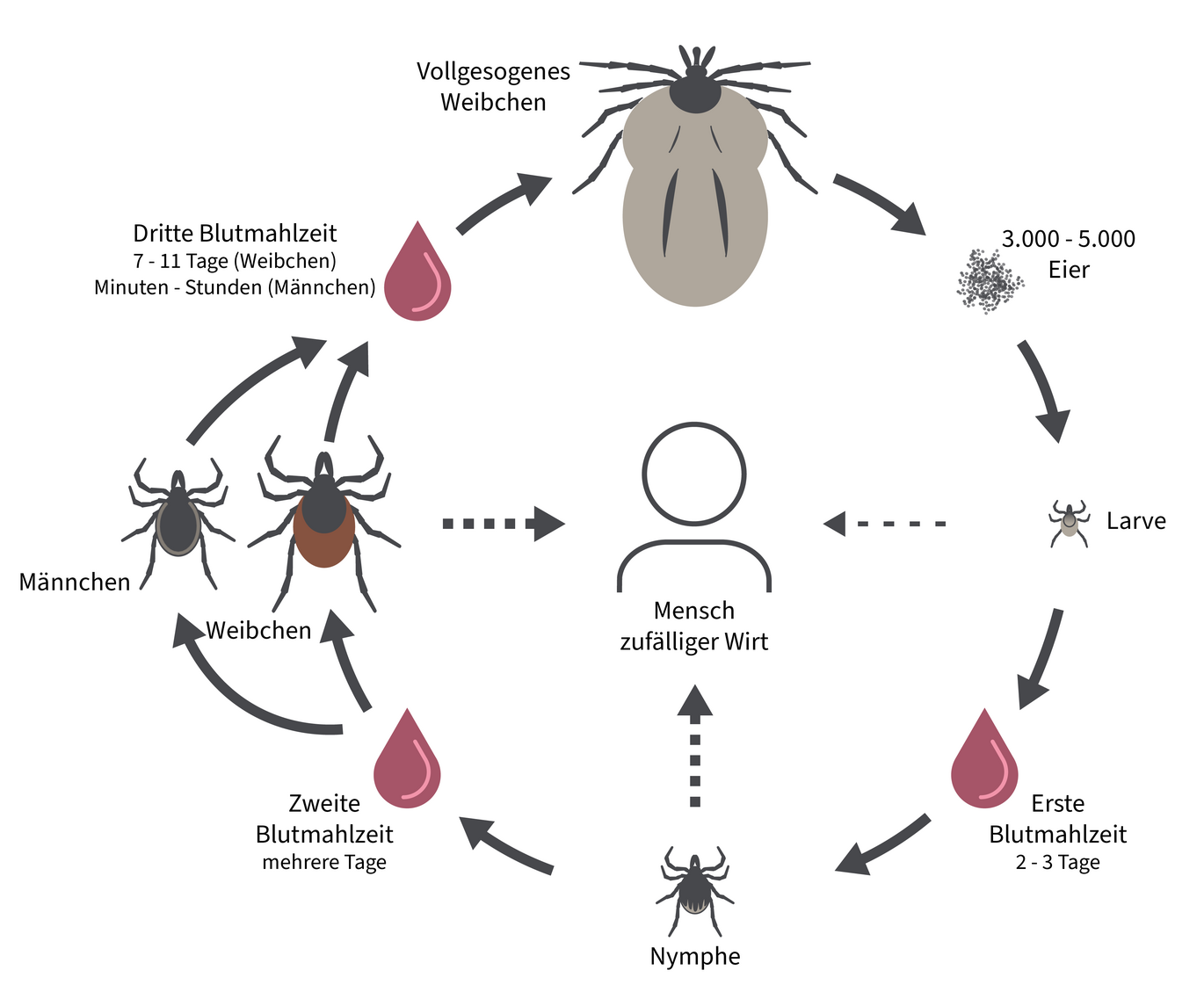

At each stage of development, the tick takes a blood meal, sucking blood while anchored in the host skin for several days. Ticks feed on the blood of mammals (including humans), birds, reptiles and amphibians. During the sucking process, the tick's body swells and becomes spherical. Once the tick is full, it drops to the ground where it digests the blood meal and sheds its skin to the next stage.

Larva, nymph, adult tick

1st stage: larva, gender-neutral.

The tick larva hatches from one of the approximately 3,000 eggs laid by the female. It has only three pairs of walking legs and appears pale skin-colored to transparent. The tick larva seeks out small rodents or birds, bites for the first time, and sucks for about two to three days until it drops and molts into a nymph after a few months. After molting, the larva enters the next stage.

The larva, which requires moisture, is found close to the ground and up to a height of about 10 cm. Here it encounters its preferred hosts: small rodents such as red-backed voles, yellow-necked voles, and wood mice.

Stage 2: Nymph, sexually neutral.

The nymph, now with four pairs of walking legs, wears a sturdy chitinous carapace after molting. Usually, the nymph overwinters in the Central European climate before seeking the second intermediate host for further development into a sexually mature tick. The nymph takes its second blood meal from larger rodents such as squirrels or medium-sized mammals such as cats, rabbits, or foxes. Nymphs also sting humans. Once the nymph has chosen its place on the intermediate host and bites, it sucks itself full of a pulpy mixture of blood and tissue for several days, drops, and sheds its skin to become an adult tick.

Nymphs climb higher on plants than larvae. They reach a height of up to 50 cm above the ground and reach larger animals.

Stage 3: Adult tick ♀ or ♂.

After the nymph molts, the adult tick is expressed as female or male. The adult female tick infests large wild animals, domestic animals, and humans for the final blood meal. The sucking process of an adult female tick takes seven to eleven days and its own body weight can increase up to one hundred times. Using attractants, the sucking female signals the adult male that she is ready to reproduce. When mating, the attracted male climbs under the female's abdomen to deliver a sperm packet into her sexual orifice.

Egg-laying

The fertilized, fully suckled female drops from the final host after just over a week and seeks a protected place on the ground to lay her eggs. The eggs are covered with a waxy protective layer. This protects the fresh egg from drying out. After laying the eggs, the female dies and the cycle begins again.

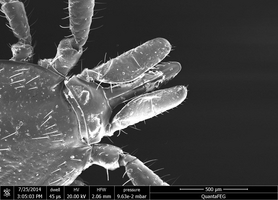

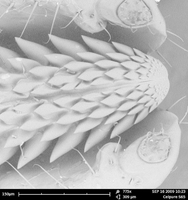

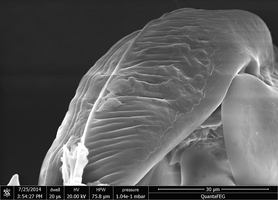

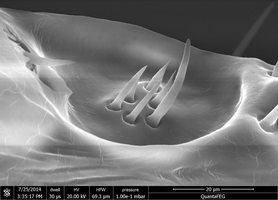

Blueprint of the tick

Stinging proboscis and adhesive organ

The mouthparts of the tick consist of a stinging apparatus with stinging proboscis (hypostome), jaw feelers (chelicerae) and jaw palps (pedipalps). At the end of the leg is the adhesive organ with two claws and an adhesive lobe. The claws provide grip on rough, the adhesive lobe on smooth, surfaces. The Haller's organ is used to find the host. In the pit on the last leg segment of the foremost pair of legs, sensory bristles of the unique and highly sensitive organ emerge. This chemoreceptor senses substances such as ammonia, carbon dioxide, lactic and butyric acid and detects approaching hosts.

As natural enemies of ticks have been identified so far:

- Fungal species such as Metarhizium anisopliae and Beauveria bassiana, which grow on ticks and kill them.

- Nematodes, which infest and kill ticks.

- Pea wasp(Ixodiphagus hookeri), which lays eggs in the tick. Hatched wasp larvae eat ticks from the inside

Found a tick?

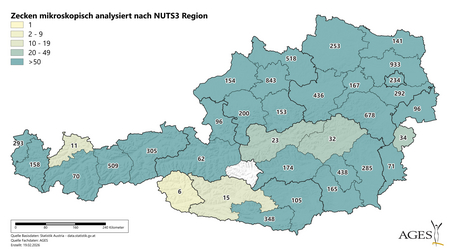

As part of a current research project, you are invited to participate as a citizen scientist in the national tick surveillance programme by sending us any ticks you find. These will be identified microscopically by experts in order to determine the species. Some of the samples received are analysed molecularly for the presence of pathogens using PCR. This helps us to continuously collect data on the distribution of ticks and their pathogens throughout Austria and the results are published regularly.

We would like to point out that the legal regulations for the transport of dangerous goods by post must be observed: Live ticks may not be sent by post. Dead ticks are considered "exempted veterinary samples" and must be packaged accordingly (see dangerous goods brochure of the post office) and sent to the following address: AGES, Department for Vector-borne Diseases, Währinger Straße 25a, 1090 Vienna.

Live ticks can only be handed in at the listed drop-off points (further drop-off points are currently in preparation):

-

Vienna: AGES, Währinger Straße 25a, 1090 Vienna, for the attention of Ms Anna Schötta. Please deposit directly in the tick drop-off box to the right of the entrance (around the clock)

-

Lower Austria: AGES, Robert Koch Gasse 17, 2340 Mödling, for the attention of Dr Georg Duscher

-

Upper Austria: AGES, Wieningerstraße 8, 4020 Linz, Austria, drop-off option Mon-Thu 7:30-15:30 and Fri 7:30-15:00

-

Salzburg: AGES, Innsbrucker Bundesstraße 47, 5020 Salzburg, delivery possible Mon-Thu 8:00-16:00 and Fri 8:00-12:00

-

Styria: AGES, Beethovenstraße 6, 8010 Graz, drop-off option Mon-Fri 7:00-15:00 at the registration desk

-

Tyrol: AGES, Technikerstraße 70, 6020 Innsbruck. Please follow the arrows to drop off samples (around the clock)

-

Carinthia: Landesmuseum Kärnten, Liberogasse 6, 9020 Klagenfurt. Tick mailbox is located at the fence and is accessible around the clock.

Please also provide us with the following information when you hand in your tick:

- Date (date of discovery or removal)

- Postcode and place/area where the tick was found (as accurately as you know and wish to provide)

- Was the tick removed from a host (human, animal)? If yes, from which one?

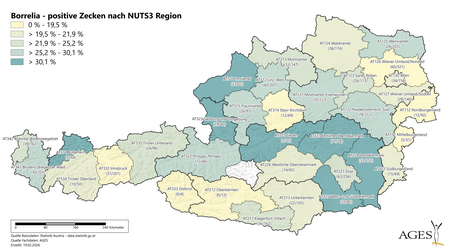

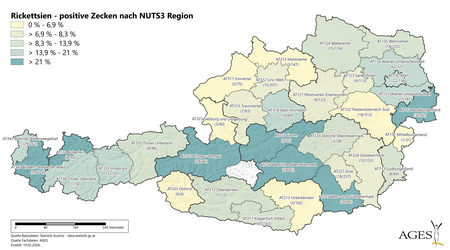

In the case of a tick submission, you agree that the exact location of the tick will be noted for internal purposes and the affected region (but not the exact location) will be coloured in on a map of Austria (resolution: NUTS3 level). If you suspect the presence of a Hyalomma tick("giant tick") without the possibility of submitting it, please contact us and send a photo of the tick to our email address zecken@ages.at.

We would like to point out that this is a tick surveillance project and that we cannot provide individual results of the tick tests. The detection of pathogens in ticks is not a reason for antibiotic treatment.

What is the best way to pack ticks?

Ticks must be packaged in an escape-proof manner.

Ticks that are not yet fully engorged - i.e. still "flat" - can be fixed on one side with adhesive tape on a sheet of paper.

Ticks that have already sucked blood must be packed in pressure-resistant, rigid containers (e.g. small jars, small plastic boxes, screw-top containers, etc.).

Please hand in the tick in a sealed envelope (this also applies if you hand it in at one of our drop-off centres) together with information on the date, location and whether it was removed by a host (if so, from which host) and address this envelope to AGES GmbH, Department for Vector-borne Diseases - Ticks, Währinger Straße 25A, 1090 Vienna.

Live ticks may only be handed in at our collection points and may not be sent by post. We therefore recommend freezing the ticks overnight before sending them by post. Temporary freezing also makes it possible to collect ticks over a longer period of time and send them to us later, provided they are well labelled.

What condition should the tick be in?

The best ticks for us are undamaged, still alive and have not yet bitten. Then the quality for subsequent examination is the best. After morphological species identification, these are also examined for pathogens using molecular biology. Ticks that are now dead but have not bitten are also suitable for examination for Borrelia.

We are also happy to accept ticks that have already bitten but can be removed relatively undamaged. As the blood of the host is also present in a fresh blood meal and there is a possibility of damage to the tick, a decision is made after the microscopic examination and on the basis of the data provided as to whether the tick will also be analysed using molecular biology.

Completely damaged ticks (tick body no longer intact, crushed) are unfortunately not suitable for our analyses. If you suspect the presence of a Hyalomma tick ("giant tick"), please send a photo to zecken@ages.at. We will get back to you as soon as possible.

How do I store the tick until it is delivered?

After the tick has been well packaged, you can store it at room temperature for a few days until it is released. However, it is best to store it in the refrigerator (4-8 °C). The refrigerator is also better for ticks that have been soaked in blood (e.g. from pets), as this can delay the laying of eggs.

If you are unable to deliver ticks to us within a month, you can also freeze them until delivery (-20 °C). Repeated thawing and refreezing should be avoided at all costs, as this can impair the sample quality. For short-term storage, the refrigerator is preferable.

What is the tick analysed for in the laboratory?

The current project includes vector screening to determine which tick species occur where and when in Austria and pathogen screening, which currently includes molecular biological testing for borrelia. This pathogen screening is to be extended to other pathogens in the future.

I always have a lot of ticks from different regions - can I collect them over a longer period of time and deliver them all together?

The ticks should be as fresh as possible for certain analyses (see question on storage). It is also possible to send ticks directly to Vienna(contact tick study).

If you collect ticks over a longer period of time (more than 1 month), freeze the ticks during this time (-20 °C). It is then all the more important that the data on the ticks can be easily assigned. Please note if your tick has already been frozen.

Why should you take part here?

Your tick donation is completely voluntary and is purely for research purposes. Every additional tick helps us to generate data from as many different regions in Austria as possible. Your contribution also enables us to generate data for your region, which will be published on our homepage (under "Tick study - results") as part of the study.

Why are no individual results reported?

Pathogen detection in a tick has no medical relevance and says nothing about the risk of infection. Even if a tick tests positive, this does not mean that pathogens have been transmitted (e.g. it could be positive because "nothing" has been transmitted yet). Conversely, a negative result does not rule out the possibility that pathogens have been transmitted (e.g. they are no longer detectable in the tick due to the blood meal). Therefore, ticks that have not yet bitten are also best suited for this study, as the result is then not falsified by a blood meal. The most effective way to prevent infection is to remove the tick as soon as possible.

Zeckenstudie: Zwischenergebnisse

Die Ergebnisse des Jahres 2024 wurden in unserem Jahresbericht Zeckenmonitoring in Österreich 2024 zusammengefasst.

Im Jahr 2025 erreichten uns 8.298 Zecken aus Österreich.

Den größten Anteil der Zecken stellten Zecken der Gattung Ixodes (96,4 %), gefolgt von Dermacentor (3,1 %) und Haemaphysalis (0,5 %). Die meisten Zecken erhielten wir aus Niederösterreich (35,1 %), gefolgt von Oberösterreich (22,5 %), der Steiermark (13,4 %), Tirol (10,9 %), Kärnten (5,6 %), Vorarlberg (5,4 %), Wien (2,8 %), dem Burgenland (2,3 %) und Salzburg (1,9 %).

Es wurden 3.838 einheimische Zecken auf Krankheitserreger untersucht und folgende Infektionsraten festgestellt: Lyme Borrelien – 23,8 %, Rickettsien – 12,9 %, Spiroplasma ixodetis – 9,6 %, Anaplasma phagocytophilum – 7,8 %, Neoehrlichia mikurensis – 4,8 %, Borrelia miyamotoi – 2,4 % und Francisella tularensis – 0,1 %.

Es wurden 2025 neun Riesenzecken (Hyalomma marginatum) gemeldet, von welchen vier mit einem Kroatien-Aufenthalt und eine mit einem Griechenland Urlaub in Verbindung standen. Drei weitere wurden ohne Reisegeschichte in der Steiermark (2) und in Kärnten (1) gefunden. Für eine Hyalomma Zecke wurden uns leider keine Informationen übermittelt. Sieben dieser Zecken wurden im Labor auf Krankheitserreger untersucht. Alle wurden negativ auf das Krim-Kongo-Hämorrhagische Fieber Virus getestet. Drei davon (zwei aus Kroatien und eine aus Weiz in der Steiermark) waren positiv für Rickettsia aeschlimannii.

Weitere Details erscheinen demnächst im Jahresbericht.

Ein großer Dank geht an alle Citizen Scientists, welche fleißig Zecken gesammelt und bei uns abgegeben haben, sowie an die vielen Kolleg:innen der AGES und diversen externen Institutionen, welche maßgeblich an der Logistik beteiligt sind und beim Projekt mithelfen.

Tick lurks near the ground

The tick does not fall from trees, but lives on the ground on the low vegetation. There it lies in wait for a passing animal or human. If the host passes the lurking tick, it allows itself to be stripped from the plant and clings on. The risk of shedding a tick is much lower in winter than between March and October.

Children are particularly at risk

Children are at increased risk because of their disposition and size. This is because children like to play where ticks are found: in undergrowth, along forest edges, in tall grass. Ticks like to settle in the head area of children.

Preferred living conditions

Ticks are found throughout the year, but are more common in the spring and fall. During the summer and winter periods, when it is too hot, too dry or too cold, the tick seeks shelter on the ground. If the ground is vegetated and covered with a litter layer of dead materials, the tick can hold on well. Ticks survive brief freezes at minus 20 degrees Celsius. As soon as weather conditions permit, they climb back up onto the vegetation and lie in wait for a host.

Ticks have spread with climate change. The altitude limit of 1,000 meters above sea level has long ceased to exist. Individual sites are higher than 1,500 meters above sea level.

Myths about ticks

"Ticks drop from trees onto their victims."

On the one hand, ticks allow themselves to be stripped from the host/human, but on the other hand, ticks live close to the ground and rarely climb more than a meter in height. Because ticks travel only short distances, they tend to stay close to the ground, lurking on grasses, shrubs and in the herb layer (first layer of vegetation above the ground) for hosts for their next blood meal. Read more here.

"Ticks pretreated with oil, butter and glue are easier to remove."

Use only tapered tick tweezers, a tick hook, or have a health care professional remove the tick. Chemical treatment is not recommended because ticks suffocate very slowly and pathogens such as Borrelia can be transmitted during this time. You can read more about this here.

"I can only get infected with a tick-borne disease in high-risk areas."

Tick hazard maps often show TBE risk areas. These are areas where ticks are particularly likely to carry the tick-borne encephalitis pathogen. But anywhere ticks are found, a tick can carry pathogens.

"I just need to protect myself from ticks in the summer."

If the temperature and humidity are right, the tick can be active year-round. Generally, ticks are most comfortable from spring through fall, and that's when the risk of a tick bite is greatest. Ticks like temperatures of 10 to 20 degrees Celsius and humid weather. Read more here.

"Vaccination is effective against all tick diseases."

Unfortunately, this is not true. Vaccination effectively protects against infection with the tick-borne encephalitis virus. However, tick vaccination does not protect against infection with the Lyme disease bacterium. Only preventive measures such as appropriate clothing, the use of repellents and tick control during and after outdoor activities can help.

Contact

Leitung

Priv.-Doz. Dr. med. Mateusz Markowicz

- mateusz.markowicz@ages.at

- +43 5 0555 37204

-

Währinger Straße 25a

1090 Wien

Priv.-Doz. Dr. Georg Duscher

- georg.duscher@ages.at

- +43 50 5552 5408

-

Robert Koch Gasse 17

2340 Mödling

Please direct any questions about the tick study to zecken@ages.at

Last updated: 02.02.2026

automatically translated