Summary

Influenza activity is at a moderate level and the positivity rate is falling significantly. RSV detections have been on the rise since the end of December, and there has also been a significant increase in hospital admissions. SARS-CoV-2 is circulating at a low level.

Measles is no longer considered eliminated in Austria, and five other European countries have also been stripped of their elimination status.

In several countries worldwide - including Austria - various infant formula products are currently being recalled after the toxin cereulide was detected.

India and Bangladesh have reported cases of the Nipah virus, and several countries in the region have stepped up health screenings at airports as a result.

The topic of the month introduces the hepatitis A virus and looks at the outbreak in Austria and Europe in 2025.

In the news, we report on the first detection of avian influenza in European dairy cows, the final withdrawal of the USA from the WHO and the end of the Marburg virus outbreak in Ethiopia.

Influenza

Influenza activity is declining significantly. Influenza detections in the sentinel system are declining, the peak of the flu epidemic has passed. AGES wastewater monitoring also shows a significant decline, both in the measured values and in the number of wastewater treatment plants with positive samples for influenza. Influenza A has accounted for almost all of the influenza detections to date. At the beginning of the season, the circulation was largely determined by subtype A(H3N2). In recent weeks, the proportion of subtype A(H3N2) has decreased, while A(H1N1) has increased. The distribution is currently balanced. Influenza B has so far only been detected in isolated cases.

Hospital admissions with influenza have been decreasing since the beginning of the year: 305 admissions to normal wards were recorded at the end of January, compared to 882 four weeks earlier. As corrections and late registrations are to be expected on an ongoing basis, the data may still change.

Influenza circulation is high in the European Union and the European Economic Area (EU/EEA). The peak appears to have been passed in some countries, and in some countries influenza activity is approaching its peak. Hospital admissions have been decreasing overall since the beginning of the year. As in Austria, there is also a co-circulation of influenza subtypes A(H3N2) and A(H1N1) at European level.

The best preventive measure against severe influenza is the annual influenza vaccination. The currently circulating subclade K has genetic changes compared to the A(H3N2) vaccine strain selected for vaccination. Initial data on vaccine effectiveness indicate that the seasonal vaccines available in the EU offer protection against infection with influenza A(H3N2). These results are consistent with findings from England. However, a final assessment of the effectiveness of vaccination can only be made retrospectively after the end of the season.

In Austria, vaccination against influenza (real flu) is recommended from the age of 6 months and is available free of charge for all age groups in the public vaccination programme. The vaccination is particularly important for people with health risks for a severe course of the disease and their contact persons/household contacts, as well as for people who have an increased risk of infection due to life circumstances (e.g. pregnant women) or occupation. A nasal vaccine is available especially for children. Details can be found at www.impfen.gv.at/influenza and in the current vaccination plan for Austria 2025/2026.

In episode 003 - Influenza & Co: How do I surf safely through the flu wave? of the AGES podcast "Courage to take risks", infection epidemiologist Fiona Költringer explains what the flu is all about and how you can best protect yourself against it.

RSV

Since the end of December, detections of the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in the in the sentinel surveillance system has increased particularly strongly in the last two weeks. Positivity has been above 10% since the end of January. Hospital admissions with RSV infections rose sharply at the end of January: with 139 admissions to normal wards in week 5, there were more than twice as many as in the previous week. In wastewater, the development is characterised by an upward trend.

In the rest of the EU and the EEA, RSV circulation is elevated and continues to rise. The season is therefore starting later than in the last two years.

Infants and young children and people over the age of around 60 are at a particularly high risk of becoming seriously ill with an RSV infection and being hospitalised.

There is currently no approved RSV vaccine in the sense of active immunisation for children. However, there are monoclonal antibodies for passive immunisation: Beyfortus (nirsevimab) is licensed and recommended for the prevention of lower respiratory tract RSV disease in neonates, infants and young children during their first RSV season and in children up to 24 months of age who remain susceptible to severe RSV disease during their second RSV season. It is also available in 2025/26 in the free childhood vaccination programme of the federal and state governments and social insurance. A vaccination for pregnant women is also approved for the passive immunisation of children. The RSV vaccination is recommended for adults aged 60 and over and persons aged 18 and over at increased risk to protect the vaccinated person against RSV infections/diseases.

A vaccination for pregnant women is also approved for the passive immunisation of children. Further information on the vaccinations is available under RSV (respiratory syncytial virus) | Vaccination simply protects. and in the current 2025/2026 vaccination plan .

In the Sentinel system, the proportion of positive SARS-CoV-2 samples in mid-January is low at around 5%. The positivity rate has remained at this low level since the beginning of January. There has been a general downward trend in wastewater monitoring over the last 4 weeks. The number of hospital admissions due to severe acute respiratory infections caused by COVID-19 was around 330 per week in December and has been falling since the turn of the year. In week 5, 95 admissions to normal wards were registered. In the EU/EEA, SARS CoV-2 is circulating at a low level in all age groups. The impact on hospital admissions has so far been limited.

The COVID-19 vaccination is available free of charge in Austria and is recommended for anyone aged 12 and over who wants to reduce the risk of a potentially severe course of the disease. You can find more information on the vaccination and the indications in the Austria 2025/2026 vaccination plan or on COVID-19 | Vaccination simply protects.

Austria is no longer officially considered "measles-free". At the end of January 2026, the WHO announced that Austria had been stripped of the measles elimination status achieved in 2015. This means that endemic measles transmission in Austria is once again considered "re-established". This decision by the European Commission for Measles and Rubella Elimination (RVC - Regional Verification Commission) was based on the data submitted as part of the annual status update for the year 2024.

In Austria, the number of cases had risen sharply again since 2023. After 186 cases in 2023, a total of 542 measles cases were registered in Austria in the "record year" 2024. In the following year, 2025, there were signs of a slight easing with 152 reported measles cases. Two cases have been confirmed since the beginning of this year (as of 11 February 2026).

The RVC's decision also included indicators that describe the quality of the surveillance system, laboratory diagnostic clarification and the implementation of the vaccination programme in Austria. One of the core strategies for eliminating measles and rubella is to "achieve and maintain high vaccination coverage rates >95% with two doses of a measles and rubella vaccine" across the country. Austria is a long way from achieving this.

The Vienna University of Technology evaluates the immunisation coverage rates for Austria every year on behalf of the Ministry of Health. This showed that the target of 95% immunisation coverage with two vaccinations has still not been achieved for most age groups. Vaccinations are also being given later than recommended. The low vaccination coverage rates mainly affect the 2019 and 2020 cohorts, where there are likely to have been vaccination gaps due to the lockdowns and other measures to reduce contact during the COVID-19 pandemic. Especially in view of the fact that children in this age group are starting kindergarten, it is important to check their vaccination status and catch up on missing vaccinations.

At the same time as Austria, five other countries in the WHO European Region have lost their "measles-free" status: the United Kingdom, Spain, Armenia, Azerbaijan and Uzbekistan. Measles is considered endemic in 13 countries in the WHO European Region, including the EU Member States Germany, Italy, France, Poland and Romania.

The USA recorded the highest number of confirmed measles cases in over 30 years in 2025 with 2,267 cases. Due to the outbreaks reported in the USA since January 2025, the responsible commission of the Pan American Health Organisation (PAHO) plans to review the measles elimination status of the USA, together with that of Mexico, in April 2026.

Preliminary data for 2025 show a significant decrease in reported measles cases in the EU/EEA countries compared to 2024, but these figures are still twice as high as those reported for 2023. The number of measles infections usually peaks in late winter and early spring, so the ECDC recommends checking your measles vaccination status now.

The measles-mumps-rubella vaccination is available free of charge for all age groups in Austria at all public vaccination centres and from all doctors in private practice. Missing vaccinations can and should be caught up on at any age. You can find more details atimpfen.gv.at/impfungen/masern-mumps-roteln or in the Austrian Immunisation Plan 2025/2026.

Measles - AGES

Measles | MedUni Vienna

Eliminating measles and rubella in the WHO European Region: integrated guidance for surveillance, outbreak response and verification of elimination

European Regional Verification Commission for Measles and Rubella Elimination (RVC)

Various infant formula products are currently being recalled in several countries around the world, including Austria. The reason for this is the detection of cereulide, a toxin produced by the bacterium Bacillus cereus bacterium.

The cereulide toxin causes vomiting, abdominal cramps and nausea, rarely also watery diarrhoea. The symptoms usually subside within 24 hours. In very few cases, severe forms of the disease can occur. Symptoms of cereulide intoxication usually appear very quickly after consuming a contaminated infant formula: within 15 minutes to 6 hours. The effects of possible exposure or ingestion of the toxic substance are mild to moderate, depending on the age of the child. Newborns and infants under six months of age are more likely to develop symptoms and may even suffer complications such as dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, etc. Therefore, the overall risk for infants under one year of age in the EU or EEA is considered moderate in this case(ECDC, as of 6 February 2026).

An overview of the batches affected in Austria to date can be found at Infant formula: All recalls at a glance - AGES

The ECDC has received several reports of diarrhoea in infants following consumption of the products. The analysis of cereulide toxins in stool samples is not a method available for routine diagnostic purposes in clinical microbiological laboratories. So far, Belgium is the only EU country in which five infants have tested positive for the toxin. All five had consumed infant formula from a recalled batch and made a full recovery. The infant formula consumed tested positive in three cases and two samples are currently being analysed in the reference laboratory. Other countries, such as France, Denmark, Spain and the United Kingdom, have also reported some cases of diarrhoea in infants, but the link with the consumption of recalled products has not yet been established(ECDC, as of 6 February 2026).

On 2 February 2026, the European Food Safety Authority(EFSA ) published a rapid risk assessment for cereulide. Taking into account a safety factor of 100 and an additional safety factor of 3 for infants, an Acute Reference Dose (ARfD) of 0.014 µg cereulide per kilogram body weight per day has now been established for the first time. Cereulide concentrations above 0.054 μg/L in infant formula and 0.1 μg/L in follow-on formula could therefore exceed safe levels. At the end of January, a cereulide concentration was detected for the first time in infant formula in Austria that must be classified as harmful to health according to the new EFSA assessment, as the ARfD is exceeded several times. This product is one of those that have already been recalled by the manufacturer.

On 03/02/2026, Bangladesh reported a case of Nipah virus (NiV) infection from a region in the west of the country. The patient had developed fever and neurological symptoms on 21 January and was referred to a tertiary hospital a week later, where she died on the same day. On 29 January, the NiV infection was laboratory confirmed. The patient had no history of travelling, but had consumed raw date palm juice several times beforehand, a source of infection that had been described several times in past outbreaks in the country. A total of 35 contact persons identified during the investigations are currently being monitored; no further cases have been detected in Bangladesh to date(WHO, as of 6 February 2026).

Shortly before, on 26 January 2026, the Indian authorities reported two laboratory-confirmed cases of NiV infection in the state of West Bengal, in the north-east of the country and bordering western Bangladesh. The two people affected are two nurses at a hospital in Barasat. They had developed typical symptoms of a severe NiV infection at the end of December and were hospitalised at the beginning of January. Both are receiving inpatient treatment(WHO, as of 30/01/2026). A total of 196 contact persons were identified and quarantined. All contacts have tested negative for NiV(ECDC, as of 06/02/2026). Several countries in the region, including Thailand, Nepal and Cambodia, have stepped up health and symptom screening at international airports in light of the current regional situation.

At a global level, the WHO currently classifies the public health risk as low. According to the ECDC, the current risk for the European population is assessed as very low.

The Nipah virus is a zoonotic virus from the henipavirus family. Flying foxes of the genus Pteropus ("fruit bats") are considered a natural reservoir. The virus is transmitted through contact with infected animals or through food that has been contaminated by saliva, urine or other excretions of infected animals. Human-to-human transmission is also possible through close contact with an infected person. Previous outbreaks have been linked to the consumption of contaminated date palm juice, among other things. The virus has a high case fatality rate, which is estimated to be between 40% and 75%, depending on local conditions for early detection and medical care. There is currently no specific antiviral therapy or vaccination available. However, work is underway: At the end of December, Oxford University launched the world's first phase II trial of the NiV vaccine.

The first known Nipah outbreak was described in 1998 in Malaysia and Singapore in connection with infected pigs. At that time, 269 people fell ill, 101 of whom died. NiV is on the WHO list of prioritised pathogens (R&D Blueprint), which represent a major public health risk due to their epidemic potential and the lack of adequate countermeasures to date. In the AGES-Radar issue of 11.12.2025, we took a closer look at "Disease X" and these prioritised pathogens in the Topic of the Month.

Nipah virus infection - Bangladesh

Nipah virus disease - India

Nipah virus disease cases reported in West Bengal, India: very low risk for Europeans

| Occurrence | Widespread worldwide, especially in regions with inadequate hygienic conditions. Rare in Austria, especially in connection with travelling |

| Pathogen | Hepatitis A virus |

| Reservoir | Mainly humans |

| Route of infection | Either directly faecal-oral (especially in close contact) or indirectly faecal-oral (via contaminated food or drinking water, but also surfaces and objects) Asymptomatic cases, often children, can also be a source |

| Incubation period | Average 1 month, range: 15-50 days |

| Duration of infectiousness | At the earliest 2 weeks before and up to 1 week after the onset of symptoms, infants can excrete the virus for up to 6 months |

| Clinical symptoms | Initially unspecific symptoms (fever, tiredness, loss of appetite and nausea), then often right-sided upper abdominal pain, vomiting and elevated liver enzymes; often itching and jaundice. In addition, enlargement of the liver, occasionally rashes. In children under the age of six, the disease is often subclinical or asymptomatic. Fatal outcomes are rare |

| Risk groups | Children and travellers to high-endemic areas, contact persons, persons in occupational contact with faecal excretions, persons who use intravenous drugs. |

| Vaccination | Recommended for certain risk groups or as post-exposure prophylaxis after contact |

Hepatitis A has been known since ancient times and is widespread worldwide, but the incidence varies greatly from region to region. High incidences are found in areas with poor hygienic conditions, especially poor water supply, and therefore mainly in low- and middle-income countries. In such high-endemic areas, infection usually occurs in childhood; in Africa and Asia, there are regions in which over 90% of the population has been serologically proven to have been in contact with the hepatitis A virus. In industrialised countries, i.e. in low-endemic areas, this figure is around 33%. China, some countries in South America, Central and South-East Asia and the Middle East are among the intermediate endemic areas. Hepatitis A outbreaks can occur under certain circumstances in these intermediate endemic areas and in low-endemic areas.

Hepatitis A is caused by the hepatitis A virus (HAV). Despite the similar names, this virus is not related to other hepatitis viruses. It belongs to the hepatoviruses, which, like polioviruses, rhinoviruses or Coxsackie viruses, belong to the Picornaviridae. The naming of the hepatitis viruses is based on the clinical appearance of hepatitis, the inflammation of the liver, and has nothing to do with the genetic relationship. HAV was first visualised under an electron microscope in 1973. In humans, it can be divided into three genotypes (I-III) with subtypes A and B; genotypes IV-VI affect monkeys. All genotypes belong to one serotype, which is relevant for the immune response: regardless of the genotype, the same neutralising antibodies are produced and lifelong immunity remains. Like other non-enveloped viruses, HAV is very environmentally resistant and can remain infectious for weeks in food, soil or fresh and salt water. It is also resistant to temperature fluctuations and can, for example, survive deep-freezing and temperatures of up to 60 degrees Celsius. It is also less sensitive to soap. Only special disinfectants labelled "virucidal" or specifically tested against HAV effectively kill the virus.

HAV are excreted in the faeces of patients with or without symptoms; the route of infection is faecal-oral. Transmission from person to person can occur either directly through close contact or sexual contact or indirectly via contaminated water, e.g. raw seafood or frozen berries, food, surfaces or objects. The spread of the disease is therefore closely linked to hygienic conditions. Transmission via blood/blood products or when sharing blood-contaminated needles has also been described. Hepatitis A is highly contagious; a low dose of 10 to 100 virus particles is probably sufficient for infection. The first symptoms appear approximately one month after contact, but the incubation period can be between two weeks and 50 days. Affected persons who develop symptoms are contagious from two weeks before the onset of symptoms until approximately one week after the onset of symptoms. The period around the onset of symptoms is the most infectious. Children play a special role here, as they often show no symptoms and can excrete the virus over a long period of time (up to six months). All these characteristics - high environmental resistance, low infectious dose, infectiousness before the onset of symptoms, asymptomatic carriers - contribute to rapidly progressing outbreaks.

The disease itself begins with non-specific, flu-like symptoms such as fever, fatigue, loss of appetite and nausea, followed by inflammation of the liver with right-sided upper abdominal pain, elevated liver enzymes or symptoms such as itching and jaundice. In addition, the liver may also become enlarged and a fleeting rash may appear. The disease normally heals itself. Even though recovery can take months, there is no chronic liver inflammation. Mortality is low, around 0.1 to 0.3 %, but the risk increases with age and pre-existing liver disease.

Children and travellers to high-endemic areas, contact persons of hepatitis A cases, persons in occupational contact with stool excretions (e.g. in laboratories, sewer workers) and persons who use intravenous drugs have an increased risk of hepatitis A infection.

In Austria, vaccination is currently not generally recommended for children, but only for certain risk groups who have an increased risk of contracting hepatitis A (travellers; healthcare workers; men who have sex with men (MSM); social workers) or a severe course (chronic liver disease, chronic intestinal diseases), or who have an increased risk of spreading the disease (staff in food businesses or communal catering). Vaccination is possible from the age of 1 using an inactivated vaccine and is given either in two vaccine doses or in the form of a combination vaccine against hepatitis A and B in three vaccine doses. Immunity lasts for a long time after vaccination and a booster is not usually necessary. For more information on the vaccination recommendation, see the Hepatitis A chapter under "Travel/indication vaccinations" in the Austria 2025/2026 vaccination plan.

| Total number of cases | 249 |

| Incidence | 2,71/100.000 |

| Median age (IQR) | 35 (23-49) |

| Gender (M:W) | 154:94 |

| Hospitalised | 127 (51%) |

| Deceased | 4 (1,6%) |

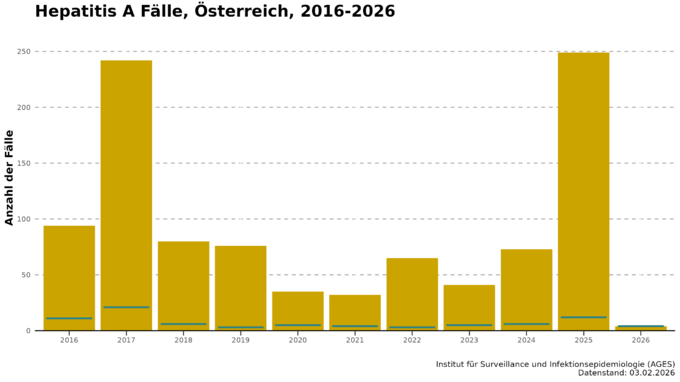

Austria is one of the low epidemic areas, mainly due to extensive adequate sanitation; infections are often acquired abroad. As a rule, around one third of cases are associated with travelling. In recent years, the incidence of hepatitis A has been less than one case per 100,000 inhabitants; in absolute figures, this amounts to between 30 and 80 cases per year (Fig. 1).

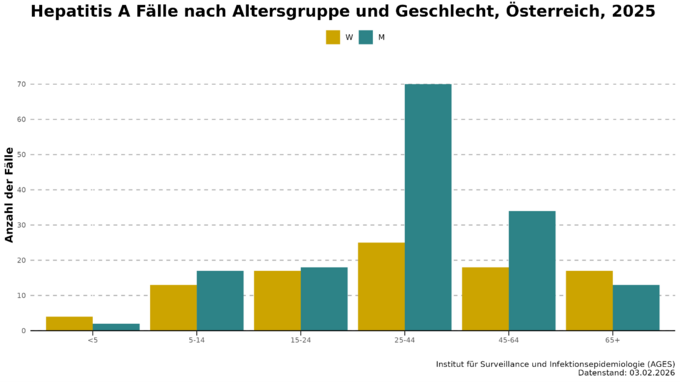

In Austria, men and middle-aged people are slightly more frequently affected by hepatitis A, while children are less likely to contract the disease (Fig. 2). Among the reported cases, hospitalisation is common, with around half of those affected having to be admitted to hospital. Admissions to an intensive care unit (0 to 2 per year) and deaths (0 to 1 per year) are rare.

Exceptions to the normally low hepatitis A incidence are the outbreak years 2016/2017 and 2025 (see Fig. 1). From the summer of 2016 to 2017, there was a global (mainly in Europe and America) hepatitis A outbreak: the incidence in Europe doubled compared to previous years, with Slovakia, Romania and Bulgaria being the most affected countries. A total of 26,294 cases were reported in the EU in 2017, mainly affecting men aged between 25 and 44. The causative viruses could be assigned to three different strains. The outbreak was mainly driven by human-to-human transmission, food played a subordinate role and MSM were disproportionately affected. In Austria, 94 and 242 cases of hepatitis A were reported in 2016 and 2017, with incidences of 1.07 and 2.74 per 100,000 inhabitants. The proportion of travel-associated cases accounted for less than a quarter in these years.

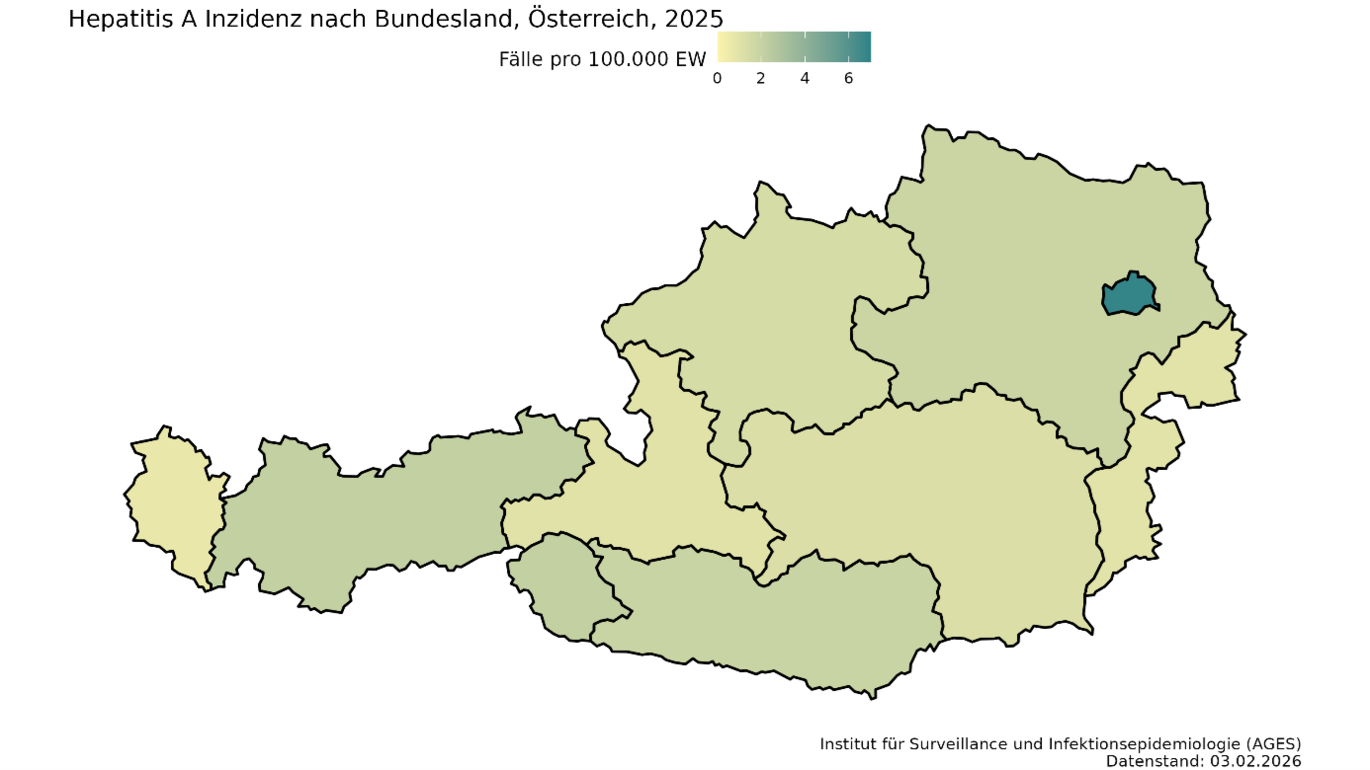

In 2025, there was another sharp rise in the number of hepatitis A cases in Austria, especially in Vienna (see Fig. 3). In March, 32 cases were already reported, and in May the number of infections was already higher than in previous years for the entire year. A total of 249 cases were reported, with an incidence of 2.71 cases per 100,000 inhabitants. Molecular biological analysis of the hepatitis A viruses by the National Reference Centre also revealed that in many cases the infection was caused by one of the two circulating HAV strains. Both HAV strains belong to the IB genotype and are closely related to each other. The two outbreaks so far include a total of 131 cases, three of which are from 2023 and 2024. Five patients (3.8%) have died as a result of the outbreak. 42% had to be admitted to hospital for treatment, four patients were cared for in intensive care. The median age of those affected was 37 years, 76% were men. The outbreak investigation was able to rule out contaminated food. As in 2017, the outbreak appears to have mainly spread directly from person to person. A strikingly high proportion of the cases surveyed were people without shelter (31%) and people who use drugs intravenously (17%). Almost a third of the cases were suspected to have been infected abroad, although different countries were stated here. One fifth of respondents had either been in contact with hepatitis A or diarrhoea sufferers and/or had high-risk sexual contact prior to infection.

It became known via the European Surveillance Portal and subsequently via a Rapid Risk Assessment by the ECDC that Austria is not the only country affected by an increase in hepatitis A cases. The ECDC reported in November 2025 that a total of over 6,000 cases of hepatitis A had been reported in European countries. Slovakia with 2,482 cases, the Czech Republic with 2,310 cases and Hungary with 1,548 cases account for the largest share. The Austrian cases are related to those from the three neighbouring countries, as they have the same outbreak strains. In all countries, groups of people who live in poor hygienic conditions or are inadequately connected to the healthcare system are increasingly affected. In addition to homeless people and people who use intravenous drugs, a particularly high proportion of people in the neighbouring countries belong to Roma communities. In Hungary and Slovakia, in contrast to Austria and the Czech Republic, more children than adults are affected. In Slovakia, the outbreak is likely to have started at the end of 2022 and peaked in 2023/2024, while in the other affected countries it did not reach its peak until late 2024/early 2025. There have also been isolated cases in Germany, Sweden and the UK.

In all countries, including Austria, there have been vaccination and information campaigns in the affected populations and among carers/treatment staff. In Austria, case numbers have been declining since a peak in summer 2025, with the last case reported in early December. It is still unclear how the outbreak will develop in an international context.

On 23 January 2026, the Dutch authorities reported the detection of antibodies against the avian influenza virus A(H5N1) in the milk of a dairy cow. The cow had previously exhibited mastitis (inflammation of the udder) and respiratory symptoms. No milk from the diseased cow has been placed on the food market and foodborne transmission is not currently suspected.

In the meantime, antibodies against the influenza A(H5N1) virus have been found in four other cows on the same dairy farm. Antibodies indicate a confirmed infection, making these the first avian influenza infections in dairy cows in Europe. The farm came to the attention of the authorities after the avian influenza virus was discovered in a cat in the vicinity of the farm. None of the exposed individuals on the farm have developed symptoms and no antibodies have been detected. Further investigations are still ongoing.

To date, there have been no confirmed human cases of influenza A(H5N1) in the EU or EEA. In the USA, however, transmissions to humans have occurred in connection with infections in dairy cows. However, these were rare and mild. The ECDC's risk assessment therefore remains unchanged: The current risk is considered low for the general population and low to moderate for people with occupational exposure (e.g. poultry farm workers) or other exposure to infected animals or contaminated environments.

A vaccine against avian influenza is available free of charge in certain facilities in Austria. Due to epidemiology, specific incidence of infection and low probability of infection, vaccination against avian influenza is currently not recommended or planned for everyone. Vaccination is recommended for people who may have (intensive) contact with infected animal populations, especially bird populations. Further information on vaccination centres can be obtained from the respective state health authorities. The vaccination recommendation for avian influenza (bird flu) is available online at sozialministerium.gv.at/impfplan.

All information on bird flu can also be found in episode 10: The chickens aren't laughing - bird flu in the spotlight of our AGES podcast Courage to take risks with expert Irene Zimpernik.

On 26 January 2026, the Ethiopian Ministry of Health officially declared the first ever Marburg virus outbreak in their country to be over after no new cases had occurred over a period of 42 days - in line with WHO outbreak control criteria. On 14 November 2025, the first cases of Marburg virus disease were confirmed in Ethiopia. A total of 19 cases were registered during the outbreak, 14 of which were laboratory-confirmed. Nine of the confirmed cases and the five probable cases were fatal(WHO, as of 26 January 2026).

On 22 January 2026, the USA officially withdrew from the WHO. In a statement dated 24 January 2026, the WHO acknowledges the withdrawal and responds to the US press release on the withdrawal. The USA has been one of the founding members of the WHO since its establishment in 1948 and was the largest contributor.

For a deeper insight into the powers and resources of the WHO: In the AGES-Radar issue of 20 February 2025, we wrote about the WHO and the planned withdrawal of the USA in the topic of the month.

The 2026 Winter Olympics will take place in Italy from 4 February to 22 February and will bring together visitors from all over the world. The ECDC has therefore published health protection advice. Travellers should check their vaccination status, especially against measles, as outbreaks have been reported worldwide and also in Italy. Travellers are also advised to protect themselves against respiratory infections such as influenza, COVID-19 and RSV and to observe basic hygiene measures. Food and water safety advice includes cooking thoroughly, washing hands and being careful with food that has been left unrefrigerated for a long time. Protection against sexually transmitted infections is also called for.

The Lombardy region has set up its own website for the 2026 Winter Olympics to provide information on emergency services, medical support and medicines.

The ECDC is monitoring this mass event as part of its epidemiological surveillance activities in close cooperation with the Italian National Institute of Health and other partners.

The AGES Radar for Infectious Diseases is published monthly. The aim is to provide the Austrian health services and the interested public with a quick overview of current infectious diseases in Austria and the world. The diseases are briefly described, the current situation is described and, where appropriate and possible, the risk is assessed. Links lead to more detailed information. The "Topic of the month" takes a closer look at one aspect of infectious diseases.

How is the AGES radar for infectious diseases compiled?

Who: The radar is a co-operation between the AGES divisions "Public Health", Knowledge Management and Risk Communication.

What: Outbreaks and situation assessments of infectious diseases:

- National: Based on data from the Epidemiological Reporting System (EMS), outbreak investigation and regular reports from AGES and the reference laboratories

- International: Based on structured research

- Topic of the month (annual planning)

- Reports on scientific publications and events

Further sources:

Acute infectious respiratory diseases occur more frequently in the cold season, including COVID-19, influenza and RSV. These diseases are monitored via various systems, such as the Diagnostic Influenza Network Austria (DINÖ), the ILI (Influenza-like-Illness) sentinel system and the Austrian RSV Network (ÖRSN). The situation in hospitals is recorded via the SARI (Severe Acute Respiratory Illness) dashboard.

For the international reports, health organisations (WHO, ECDC, CDC, ...) specialist media, international press, newsletters and social media are monitored on a route-by-route basis.

For infectious diseases in Austria, the situation is assessed by AGES experts, as well as for international outbreaks for which no WHO or ECDC assessment is available.

Disclaimer: The topics are selected according to editorial criteria, there is no claim to completeness.

Suggestions and questions to:wima@ages.at

As the response to enquiries is also coordinated between all parties involved (knowledge management, MED, risk communication), please be patient. A reply will be sent within one week.

Case numbers of notifiable diseases according to the Epidemics Act, the figures are shown for the previous month and, in each case for the period from the beginning of the year to the end of the previous month, the figures for the current year, for the previous year, as well as the median of the last 5 years for comparison (Epidemiological Reporting System, as of 11 February 2026).

| Pathogens | 2026 | 2025 | 2021-2025 (median) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | Jan-Jan | Jan-Jan | Jan-Jan | |

| Amoebic dysentery (amoebiasis) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Botulism b | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Brucellosis | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Campylobacteriosis b | 499 | 499 | 500 | 507 |

| Chikungunya fever | 13 | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| Cholera | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Clostridioides difficile infection, severe course | 56 | 56 | 96 | 66 |

| Dengue fever | 6 | 6 | 7 | 6 |

| Diphtheria | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ebola fever | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Echinococcosis caused by fox tapeworm | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Echinococcosis due to dog tapeworm | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Spotted fever (rickettsiosis caused by R. prowazekii) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Yellow fever | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Haemophilus influenzae, invasive a | 14 | 14 | 18 | 12 |

| Hantavirus disease | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Hepatitis A | 4 | 4 | 10 | 3 |

| Hepatitis B | 81 | 81 | 73 | 83 |

| Hepatitis C | 69 | 69 | 91 | 91 |

| Hepatitis D | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Hepatitis E | 8 | 8 | 3 | 4 |

| Whooping cough (pertussis) | 91 | 91 | 458 | 24 |

| Polio (poliomyelitis) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lassa fever | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Legionnaires' disease (legionellosis) d | 17 | 17 | 25 | 19 |

| Leprosy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Leptospirosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Listeriosis b | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Malaria | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Marburg fever | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Measles | 2 | 2 | 49 | 1 |

| Meningococcus, invasive c | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Anthrax | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mpox f | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Norovirus gastroenteritis b | 319 | 319 | 578 | 280 |

| Paratyphoid fever | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Plague | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pneumococcus, invasive c | 112 | 112 | 128 | 112 |

| Smallpox | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Psittacosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Puerperal fever | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rotavirus gastroenteritis b | 102 | 102 | 97 | 53 |

| Glanders (Malleus) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rubella | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Relapsing fever | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| STEC | 37 | 37 | 46 | 22 |

| Salmonellosis b | 67 | 67 | 52 | 63 |

| Scarlet fever | 14 | 14 | 21 | 2 |

| Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Shigellosis b | 29 | 29 | 28 | 9 |

| Other viral meningoencephalitis | 12 | 12 | 16 | 6 |

| Rabies | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Trachoma (grain disease) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Trichinellosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tuberculosis | 21 | 21 | 27 | 27 |

| Tularemia | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

| Typhoid fever | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bird flu (avian influenza) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| West Nile virus disease | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Yersiniosis b | 18 | 18 | 10 | 12 |

| Zika virus disease | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

a The diseases are evaluated according to the case definition. Diseases for which a case definition exists are shown, with the exception of transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. As a rule, confirmed and probable cases are counted. Subsequent notifications or entries may result in changes.

b Bacterial and viral food poisoning, in accordance with the Epidemics Act.

c Invasive bacterial disease, in accordance with the Epidemics Act.

d Includes only cases with pneumonia.

e Due to lack of case definition before 2025, only cases from 2025 onwards are shown; the median is also only calculated from 2025 onwards

f Mpox has been notifiable since 2022; the median is only calculated for the years in which notification is mandatory.

Last updated: 12.02.2026

automatically translated