Tomato leaf miner

Tuta absoluta

Profile

The tomato leaf miner is a small butterfly species from South America, which is a very difficult pest to control due to its hidden lifestyle and enormous reproduction potential. Since the moth mainly attacks tomatoes, where the feeding behavior of the larvae causes lasting damage to both leaves and fruits, it is classified as one of the most important pests of tomato crops.

Appearance

Eggs: The eggs laid by the tomato leaf miner are cylindrical, 0.36 mm long and creamy white to yellow in colour. The larvae begin to hatch just four to five days after the eggs are laid.

Larvae: The tomato leaf miner passes through four larval stages during its development from egg to pupation. After hatching, the larvae of the first larval stage are cream-coloured with a dark head capsule and are approx. 0.9 mm long. The larvae of the second to fourth larval stage are initially greenish, then slightly pink in colour. The larvae of the fourth larval stage reach a length of 7.5 mm.

Common to all larval stages is a dark-coloured shield in the front segment of the thoracic region, directly behind the head capsule. As representatives of butterflies, they also have clearly recognisable pairs of legs. The development period from hatching to pupation is about 13 to 15 days.

Pupae: Pupation can take place in the soil, on the plant, in the mine tunnels, in webs woven by the larva (cocoon), but also in the glass house construction or other objects (e.g. stored boxes). The pupal period lasts nine to eleven days.

Adults: The adult moths are 6-8 mm in size and rather inconspicuously coloured. The wings are silvery-grey in their basic colour with characteristic dark spots in the forewings. The wingspan is 8-10 mm. Typical are the almost body-length, thread-like antennae, whose individual antennae are strung together like a string of pearls.

Biology

Tuta absoluta is a species of butterfly from the palm moth family (Gelechiidae).

The moths are nocturnal and hide between the leaves of plants during the day. One female can lay up to 260 eggs. The eggs are laid on the leaves and stems of the host plants, but preferably on the underside of the leaves. The tomato leaf miner requires a minimum temperature of 9 °C for its development. At 14 °C the development period is 76 days, at 27 °C only 24 days. Up to twelve generations can develop per year.

The tomato leaf miner can overwinter in glasshouses at all stages of development. If there is sufficient food available for the larvae, they do not go through a diapause (dormancy).

Damage symptoms

After hatching, the larvae prefer to penetrate the leaves. Further development takes place in the plant tissue, whereby the feeding activity results in characteristic spot-shaped galleries in the leaves. The larva only feeds on the ground tissue of the leaves, the outermost leaf layer remains undamaged, making the feeding sites appear transparent.

The larvae can leave the leaf mines and infest stems and fruit. If fruits are infested, the yield and fruit quality can be significantly reduced - both through direct feeding activity and through the colonisation of the wounded plant organs with secondary pathogens. If stems and trunks are infested, deformities and growth inhibition occur on the plants.

A heavy infestation with T. absoluta leads to complete leaf death and can result in the total failure of a crop.

Possible confusion

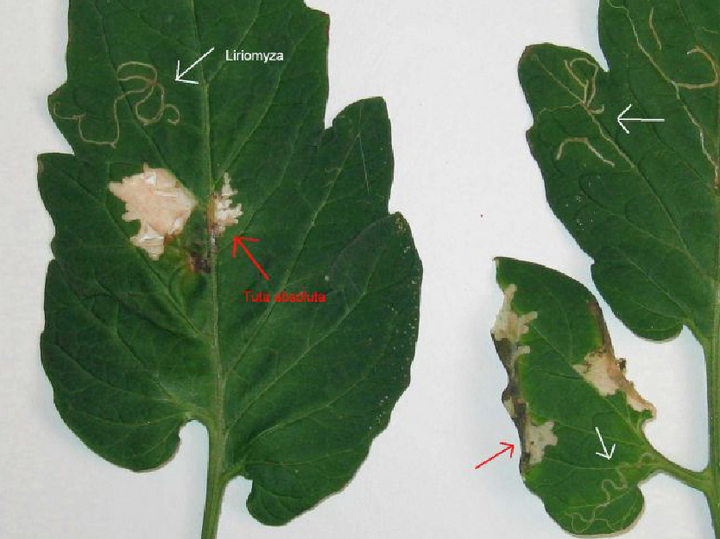

The following pests can easily be confused with the tomato leaf miner due to their similar symptoms after infestation of the host plants and their appearance:

leaf miners (Agromytidae, Diptera):

- The larvae of leaf miners also feed on leaves, but usually create serpentine mines inside the leaves. The mines of the tomato leaf miner, on the other hand, are characteristically spot-shaped.

- In contrast to the tomato leaf miner, the larvae of the leaf miner have no recognisable pairs of legs and head capsule; they also remain whitish-creamy until they pupate (boll pupa) and do not change colour.

Cotton bollworm(Helicoverpa armigera):

- The boring holes of both pests could be confused with each other. However, in contrast to the tomato leaf miner, the holes of the cotton bollworm have a significantly larger diameter of 5 to 10 mm (tomato leaf miner: 2 to 3 mm)

- In contrast to the tomato leaf miner, the larvae of the bollworm have longitudinal bands and hardened bases with bristles on them.

Host plants

The main host plant of the tomato leaf miner is the tomato(Lycopersicon esculentum). However, damage has also been observed on other members of the Solanaceae family in cultivated, ornamental and various wild plants:

- Potato(Solanum tuberosum): damage only to aboveground parts of the plant, does not affect tubers.

- Melanzani(S. melongena): infestation under laboratory conditions

- Common datura(Datura stramonium)

- Wild tomato species: Lycopersicon hirsutum, L. peruvianum

- wild plants: S. lyratum, S. elaeagnifolium, S. puberulum, thorny datura(Datura ferox), blue-green tobacco(Nicotiana glauca)

- melon pear(S. muricatum)

- Black nightshade(S. nigrum)

Distribution

Originally, the tomato leaf miner originates from South America, where it is considered the most important tomato pest in open field as well as in protected cultivation (foil tunnels and greenhouses). It has been known as a pest in large parts of South America since the early 1980s.

The first occurrence on the European continent was reported from Spain in 2006. In the 2007 growing season, massive yield losses were reported from all tomato growing areas in the coastal region. Since then, it spread very rapidly to countries in the Mediterranean region and North Africa, where it causes significant damage to tomato crops. In the meantime, occurrences are known in large parts of Europe as well as in parts of Africa and Asia. In Austria, the first occurrence was detected in Burgenland in 2010.

Spread and transmission

According to a risk analysis of phytosanitary significance carried out in the Netherlands, the highest risk of movement into a non-infested area is posed by the import of tomato fruits, including their packaging and transport material. All developmental stages of T. absoluta can be introduced. Tomato imports, particularly from Spain, the Netherlands, Italy and Morocco, therefore pose a particularly high risk.

The risk of introduction through the import of tomato and melanzani plants, as well as ornamental plants from the nightshade family(Solanaceae), is considered to be low. Under favourable conditions, the tomato leaf miner can spread naturally for several kilometres by drifting with the wind.

In greenhouses, the probability of the tomato leaf miner becoming established is very high if a year-round crop of tomatoes or other host plants is grown and food is therefore permanently available for the pest. In summer, several generations can also develop in an open-air crop of tomatoes and host plants. In winter, establishment in the open in our latitudes is rather unlikely due to winter conditions with frosts. However, in mild winters, the potential for overwintering outdoors in sheltered places (e.g. in compost) cannot be ruled out.

Prevention and control

Measures/controls

- Immediate inspection of host and young plants for possible infestation upon purchase

- Regular infestation checks in the crop

- Hygiene in and around the farms (remove plant material and weeds, especially from the nightshade family)

- No overwintering of host plants in the greenhouse and removal of crop residues

Tools

- Use insect nets on the vents and in the entrance area of glasshouses

- Attach delta traps with Tuta absoluta-specific pheromone to recognise an occurrence on the farm at an early stage

- Mass trapping with water traps containing a few drops of detergent and the pheromone

Control

- Removal and destruction of infested plant parts from the greenhouse

- Confusion method with pheromone, which overlays the sexual attractants secreted by the females, thus preventing reproduction

- Use of authorised plant protection products with the indications tomato leaf miner, "biting insects" and leaf miners (see list of plant protection products authorised in Austria)

- Use of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. Kurstaki or the entomopathogenic nematodes Steinernema carpocapsae and S. feltiae

- Use of natural antagonists of T. absoluta such as the predatory bug(Macrolophus pygmaeus)

Phytosanitary status

T. absoluta is not listed as a quarantine pest in the EU, but is included by the EPPO in the "A2 List of pests recommended for regulation as quarantine pests" by the EPPO.

Last updated: 27.10.2025

automatically translated